There is plenty of advice on the Internet about what you should do for your college apps.

But what about common pitfalls you should avoid?

Here are 11 unconventional college application red flags that will weaken your application and hurt your admissions chances:

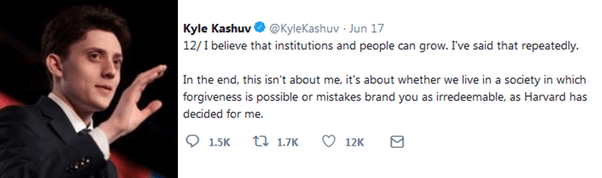

1. Offensive social media posts

Colleges have increasingly rejected and rescinded admissions offers after discovering offensive social media posts.

Parkland shooting survivor Kyle Kashuv had his Harvard admissions offer rescinded in 2019. (Source)

According to a 2017 survey of admissions officers , 14% of colleges rescinded at least one student’s admission in the previous two years due to negative social media posts.

Another survey found that 11% of officers “ denied admission based on social media content.”

These numbers are likely even higher in 2020, as admissions offices become more social media savvy.

Here are some specific examples:

- In 2017 , Harvard rejected 10 students after admissions officers discovered offensive memes that they had shared on Facebook.

- In 2020 , Cornell, Marquette, the University of Florida, and dozens of other colleges all rescinded acceptances due to racist social media posts after George Floyd’s murder.

2. Wrong major

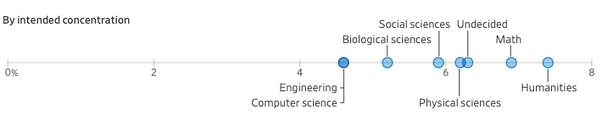

Students who demonstrate interest in different majors have widely different acceptance rates at certain colleges.

This can work to your benefit, as most colleges will allow you to switch majors after enrolling.

At Harvard , students interested in “humanities” are admitted at almost double the rate as students interested in “engineering”:

At UC Berkeley , applicants intending on studying “computer science” have an 8.5% acceptance rate, compared to 17% overall.

At Carnegie Mellon , the acceptance rate of different programs ranges from 7% to 26% !

And at UCLA , the School of Engineering explicitly sorts students by intended major, as well as admits students at a significantly lower rate than the College of Arts and Sciences.

If you mention that you are interested in pursuing Major X in college, you need to have demonstrated interest in Major X in high school:

“Noting your intended major on a college application is generally a good idea, because it shows admissions committees that you have a firm direction and plan for the future ,” says Stephen Black, Head Mentor at the admission consulting firm Admissionado.

“Even if you’re not 100% sure that this will be your major—and virtually nobody is certain—it nevertheless shows that you are interested in exploring a particular field.”

What if, the week before applying, you discover that your true passion is different than what you’ve done throughout high school?

In short: Too bad.

You’re 4 years behind students who’ve pursued that passion since 9th grade.

Stick to your strengths.

Unless a school doesn’t allow you to change your field of study post-admission, sell the college on the strongest you possible.

It’s OK if you’re no longer passionate about that something when you apply — you’ll likely change your mind in college again anyway.

3. Wrong school

If you focus your application on a skill or interest that a school is known to be weaker in, then you better prove why you have a good reason to go to that school.

Convincing the MIT admissions office that their Ancient and Medieval Studies major is the ideal department for you is more of an uphill battle than claiming to want to study Computer Science.

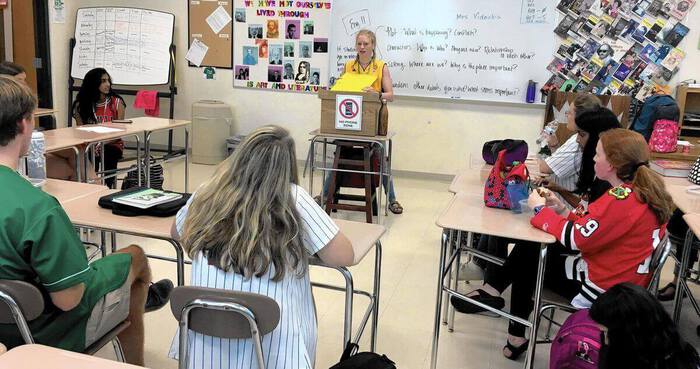

4. Submitting an “obligatory” recommendation letter

If you can get a rec letter like this, you’re golden. (Source)

Every letter of recommendation should strongly advocate for your acceptance.

If a teacher or counselor’s letter doesn’t actively advocate for you, then it will appear as if that recommender did not truly want to write on your behalf, but felt obligated in order to avoid a socially awkward situation with you.

How do you fix this?

When you ask for someone’s recommendation for college, be direct in making sure they will write you a strong letter.

Instead of asking:

"Would you be willing to write me a rec letter?"

Be straightforward and ask:

"Do you think you’d be able to write me a strong rec letter for college?"

It’s a simple change, but can be powerful.

This phrasing gives the teacher a bit more of an out if they don’t feel they can write you a strong letter. As The College Essay Guy writes:

"The word ‘strong’ gives teachers a polite out if they feel like they don’t know you well enough or don’t have time to take on your letter."

Additionally, writing a weak letter will feel like more of a personal betrayal after giving you this explicit confirmation, which can work to your benefit.

5. Submitting an “A-lister” recommendation letter

Me: “You got a rec letter from Tom Hanks? How cool!”

You: “Yeah, pretty sweet.”

A jaded admissions officer: “Yawn...Reject.”

You: “Wait…what? Did you not see the signature — That’s Tom Hanks!!”

Admissions officer: “Yep, that’s why you were rejected. This letter doesn’t mention a single specific anecdote about you. He clearly doesn’t know you. You only got this because your mom is a Hollywood agent, which speaks to your privilege. And as great of an actor as Mr. Hanks is, his words don’t carry much weight as to how amazing of a chemist you’re destined to be.”

6. Essays >15 words under the word limit.

Yes, the “word limit” is technically the maximum number of words you can write. But smart applicants know that it is also the expected number of words. Most college essays are barely 300 words.

If you can’t fill 300 words talking about the thing you want to spend 4 years of college studying, then you clearly aren’t passionate enough to be admitted.

Fifteen words is more than enough room to fit another sentence in.

7. Ignorance of privilege

If you were afforded opportunities that most students wouldn’t experience, acknowledge that. Or, at the very least, show that you understand that you were fortunate to have such experiences.

8. Insincere volunteering

If you write your essay about helping those less fortunate than you, you must be sincere and authentic in your writing.

Otherwise you risk sounding condescending, out-of-touch, and/or disrespectful.

Additionally, don’t co-opt or claim for yourself the experiences of people you help as a way to elicit sympathy; this reflects poorly on you as a person.

9. Typos

This is the easiest way to go from the Accept to Reject pile.

Print, read over, and have multiple friends/relatives read over every application before you submit.

There are 40,000+ students applying to many top colleges, usually for <2,000 spots. You can be sure that 39,000 cared enough to make sure there were no typos.

10. Different “voices” across essays.

Make sure all of your essays convey the same authentic voice. If you receive help on one essay, make sure it fits in with and sounds the same as the rest of your essays.

Make sure your Activities Section presents your achievements in the same way they’re presented elsewhere in your app and rec letters.

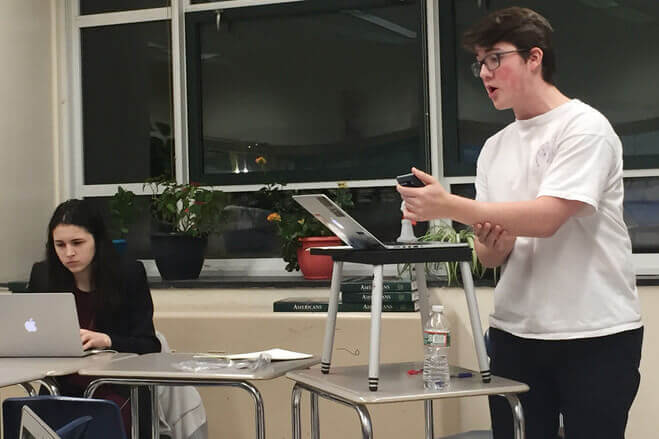

11. Unprofessional interview

A poor interview can erase a great “on paper” applicant’s chances.

The college is admitting you as a person, not a transcript, so failing the interview can make even the most impressive achievements seem fake or exaggerated.

Some of the biggest turn-offs identified by admissions officers are: not showing professionalism, dressing too casually, saying something offensive or crass, offering one word answers, and not having questions ready to ask about the interviewer’s school. ( Source 1 , Source 2 )