Last year, I was able to view my actual Harvard Admissions file through a Student Records Request, and I have several friends who work/have worked in Harvard’s Admissions Office. Thus, I've been able to learn a ton of inside knowledge about the Harvard admissions process, as well as dispel some common myths propagated by college counselors, teachers, parents, and Harvard itself.

In this article, I'll detail everything I learned first-hand about Harvard's admissions process, and tell you exactly what goes on in the committee room when your application is being voted on.

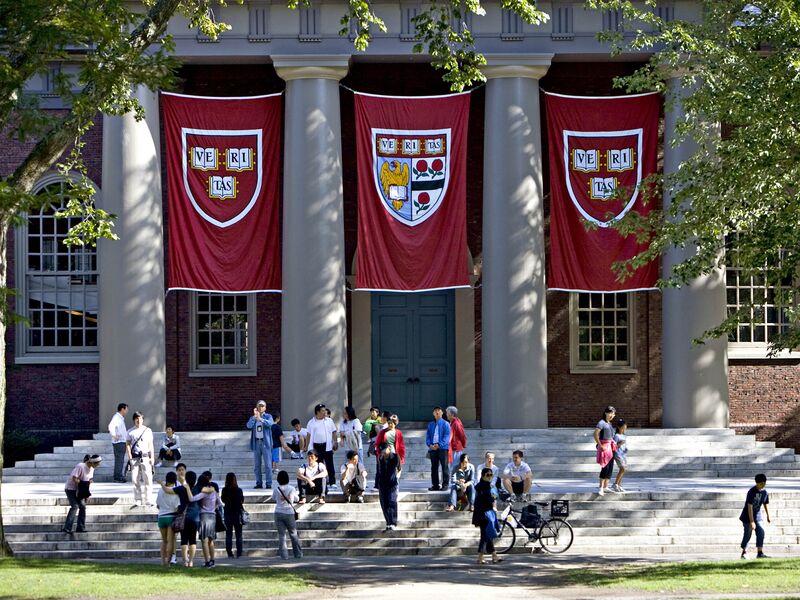

Freshmen walk through Johnson Gate while moving into the Yard during Opening Days. (Image Source)

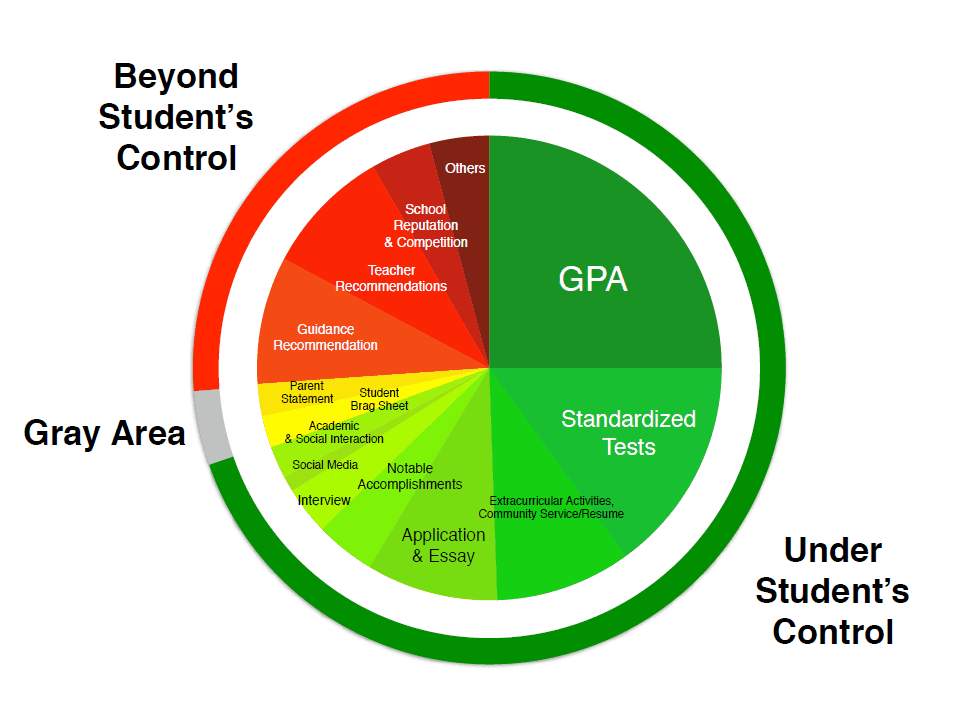

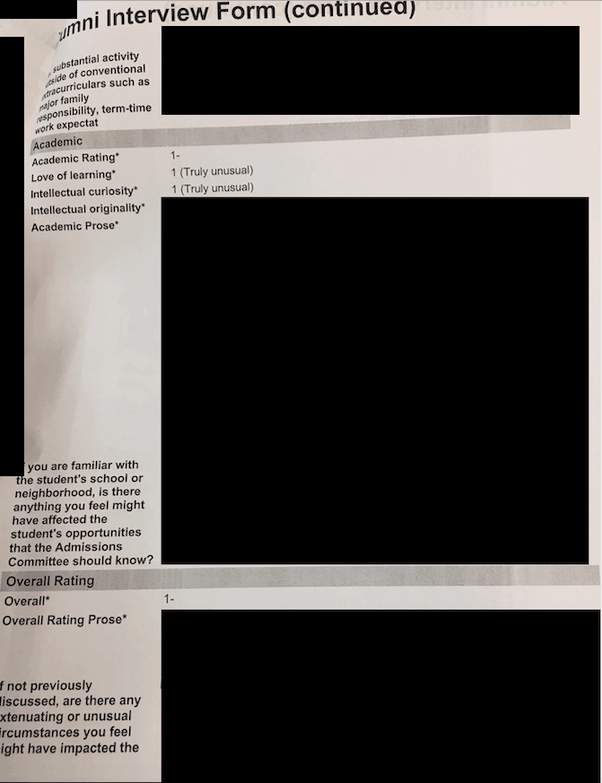

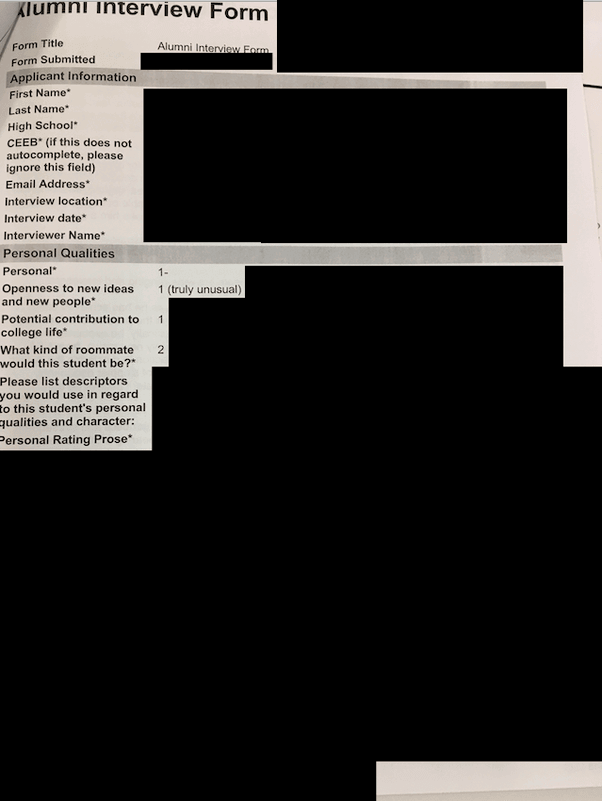

Though personal details below have been blurred out, you can get a general sense of what is on the one-page "summary sheet" that Harvard makes for every applicant in the image below. This summary sheet is given to every admissions officer so that they can quickly reference the overall strength of your candidacy when debating the merit of your admission in committee.

Screenshot of my actual Harvard Admissions file. Sections of the summary sheet have been annotated to describe what you will be graded on.

The Harvard Admissions committee will grade you on 4 metrics . They are as follows:

- Academics

- Extracurriculars

- Personal Qualities

- Athletics

For each of these metrics, you will be assigned a score of 1–6, where 1 is the best and 6 is the worst.

So which metric you should be optimizing for?

According to a friend who worked in the Admissions Office, it is the "Personal Qualities" metric that is the most underrated by applicants.

In fact, "Personal Qualities" actually ends up having the biggest impact on borderline admissions decisions.

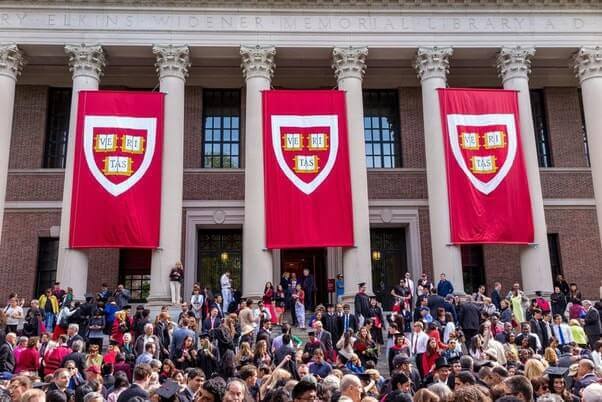

View of Dunster House, a Harvard undergraduate dorm, from across the Charles River (Image Source)

The reason for this is simple — if you’re a 1 in any of the other categories, you’re most likely going to get accepted anyway. (1) Recruited athletes (with a 1 in “Athletics”) will receive a likely letter from their coach months before admissions decisions come out, and are essentially guaranteed a spot. (2) Academic superstars who’ve published papers, proven unsolved theorems, or won prestigious competitions are also a pretty solid lock to be included in the incoming class. (3) Finally, students who’ve excelled in leadership positions in intense extracurriculars , i.e. founding a company or leading a charity or getting elected to a national position of a high school organization, are also much more likely to be admitted.

Harvard’s overall acceptance rate has gone down every year for the past decade (Image Source)

So what if you’re not one of those kids?

Well, after throwing in spots reserved for the children of prominent politicians, billionaires, and mega-donors on the dean’s list, you now have very few spots left for amazing students who aren’t quite “prodigies.”

These students would be considered “very smart” and “Harvard material” in their high schools, but not labeled “prodigies” or “child geniuses,” and wouldn’t assume their admission is “guaranteed” by any stretch of the imagination.

According to the Washington Post, this ends up being the vast majority of applicants.

These students will get a handful of 2’s and 3’s across the four metrics. That puts them in the running for admission, but their profiles could be easily swapped out with another student who has 2’s and 3’s, and you wouldn’t be able to tell the difference.

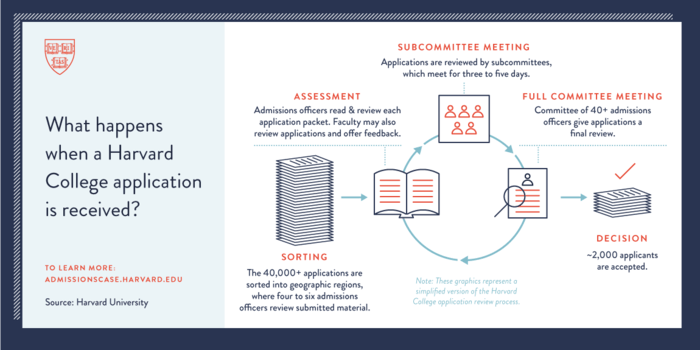

Harvard’s admissions process, according to the Harvard Admissions Office. (Image Source)

This is where Personal Qualities really stand out.

At this level, everyone is a great student, participates in extracurriculars, and has won some honors/awards. They can do the academic work at Harvard, no question.

But…

- Do they fit in at Harvard?

- Will they be the change-makers of tomorrow?

- Do they add something unique to the incoming class?

Screenshot from a Student Government campaign video that went viral earlier this year, with celebrities like Dwyane Wade, Chris Paul, and Kerry Washington retweeting the video. The students who posted this video won a surprising, come-from-behind victory to take the Presidency and Vice Presidency for 2020. Watch the video here and read a CNN article about it here

As my friend who works in the Admissions Office likes to say, Harvard’s Admissions Office prides itself on building a community, not a classroom.

Harvard wants interesting people who will get along with others, bring unique perspectives to the table, and add something unique to the make-up of the class. If another applicant has the same personality/interests/motivations as you, then your spot will get taken by that applicant. Or the 10 others with identical essays about why they want to go to medical school or why they’re passionate about a certain subject or how they coped with a family member who went through a hardship.

Your essays, teacher recommendations, and interview are incredibly important for Harvard. More so, in fact, than they are at any other Ivy League college (from what I’ve been told by friends in the Admissions Office).

If you have any more specific questions or want to see other parts of my Harvard application, feel free to message me and I’d be more than happy to answer questions.

To learn more about my Harvard admissions journey and the tips/tricks I’ve learned along the way, check out the other posts on our blog .

Or, if you want to learn these secrets yourself for your own college applications, check out the services we offer