We all know that studying for the SAT or ACT can be a time-consuming and expensive process.

That's why we’ve put together this guide to the best free SAT/ACT prep resources to help you meet your academic goals.

Before jumping into our top picks, here are a few questions you should ask yourself before you start studying:

Questions to help you orient your approach:

- How much time do I have between now and my testing date?

- How much time can I reasonably dedicate each day to studying? Is there a day per week that I can give more of my effort?

- Is there a particular section that I already know I will need to work harder on?

- How much material do I need to cover each day/week in order to make it to a certain point before my exam?

- Are there multiple test dates in the future that I can take advantage of? Or is this the last testing date I can sit?

Read on to learn about some great free resources for SAT and ACT prep.

Best Free SAT Prep

1. College Board

The College Board is the most trusted resource for all SAT prep materials since they are the creators and issuers of the SAT test.

The College Board website offers a number of free practice tests in addition to extra practice sections for math.

One of the most helpful ways to get the most out of the time you put in is to target your efforts toward not only the section that you may need most help with, but the particular sub-topics within that section that may be particularly difficult for you.

For example, if math is your lowest scoring section, you may be able to narrow down your knowledge gap to geometry or system of equations questions.

It’s important to keep in mind that during the real SAT/ACT you will have time constraints for each section.

When you are studying it is okay to take some extra time to learn a topic throughout, but remember that you won’t have that same luxury during the actual exam.

2. Khan Academy SAT Prep

Khan Academy’s SAT prep is not only endorsed by College Board, but also allows you to move at your own pace through a fairly comprehensive curriculum of SAT topics.

This will help you to further pinpoint any difficulties you may have in a particular subject and give you additional problems to solve within that subject area.

For example, you can choose to work step-by-step through the math sub-section on geometry and trigonometry, where you will find problems grouped into even more specific sub-sections such as “congruence, similarity, and angle relationships” and “circle theorems.”

Khan Academy is also a great resource for familiarizing yourself with the overall structure of the SAT, such as test-taking strategies and tips for creating your own SAT prep plan.

Khan Academy can also be particularly helpful in understanding what to expect for the SAT when it starts being offered digitally in 2024.

3. CrackSAT.net

This site offers numerous downloadable SAT practice tests in addition to reading or math specific practice tests.

The math practice tests are particularly helpful as they offer both grid in and multiple choice questions and sections with and without calculator.

The downside to CrackSAT.net is that there are usually numerous ads running on the site, which can be distracting for some users.

However, once you click on a practice test and scroll down to the questions, the ads should usually disappear.

Best Free ACT Prep

1. ACT.org

The best place to start your ACT prep journey is of course with the maker and issuer of the ACT.

You can find full length practice tests as well as modules to practice questions divided by test section.

In addition to practice materials, ACT.org also offers a free test prep guide that includes information about test dates, fee waivers, and the official answers to other preparation questions you may have.

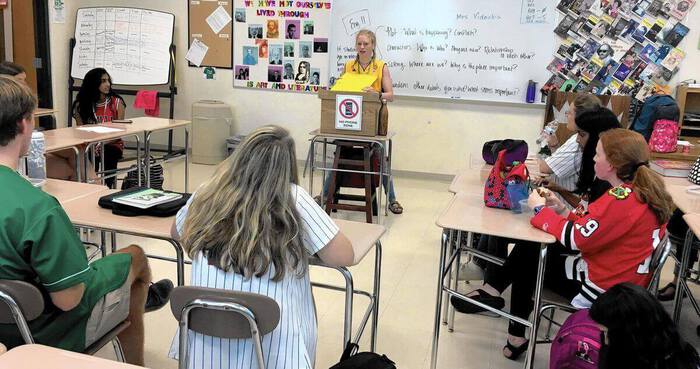

ACT.org also occasionally offers free online test-prep events and workshops that you can sign up for.

2. Varsity Tutors

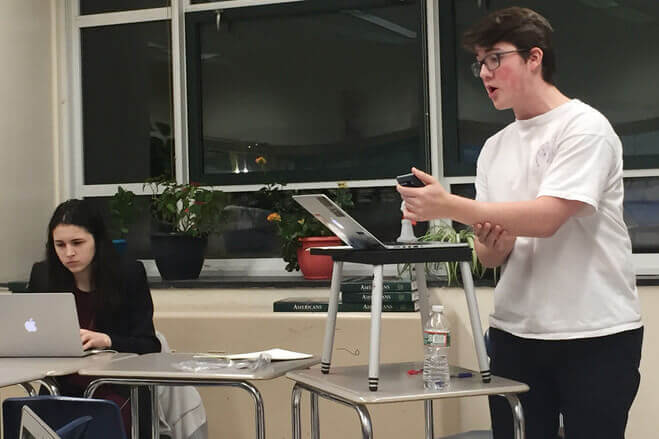

Varsity tutors is a great resource for ACT diagnostics.

With at least 10 diagnostic tests for each of the subject areas on the ACT, you can work on one section at a time in manageable chunks.

The detailed scoring results for each of the practice tests will also provide you with an understanding of which concepts you struggle with and which ones you are acing.

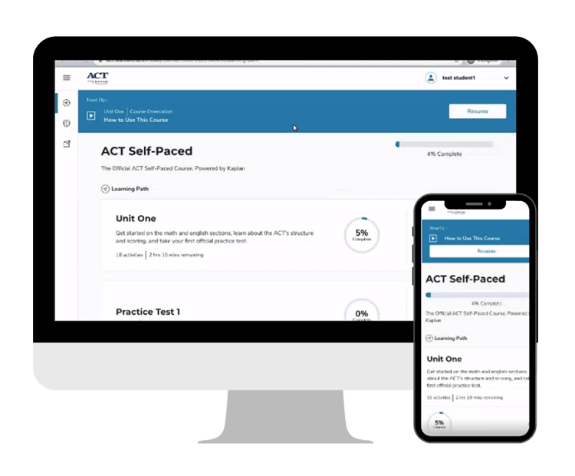

3. Kaplan

While Kaplan only offers a 1/2 length practice test, this site is particularly helpful if you are short on time but want to fit in a few practice questions each day.

Kaplan offers both an ACT pop quiz as well as a question of the day to keep your momentum going.

4. The Princeton Review

The Princeton review is one of the most popular sources for both practice materials and test-prep courses.

While many of their services are paid, you can certainly kickstart your ACT studying with their 14 day ACT prep free-trial!